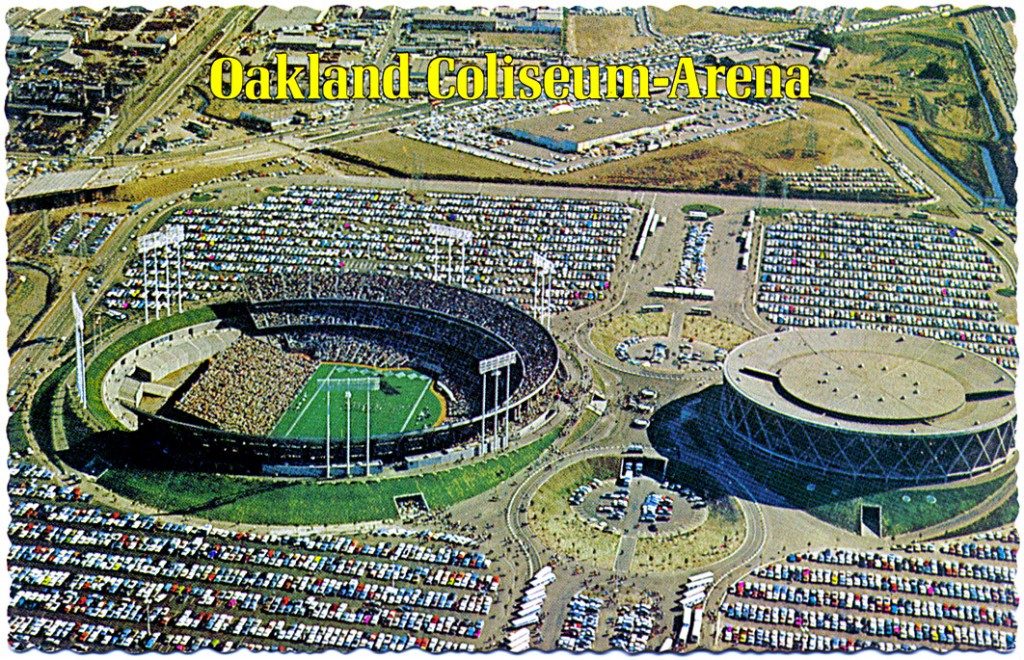

The impending departure of the Oakland Raiders from the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum means a number of things. It marks the end of the Raiders’ search for a new stadium and, with Las Vegas slated to be their new home, yet another move for a franchise that is no stranger to relocations. For the time being, it will likely mean the end of the NFL in Oakland, which opened the Coliseum for the Raiders in 1966 and invested in renovations to secure their return from Los Angeles in 1995.

The move of the Raiders will also signify something significant when it comes to stadiums, as the Coliseum is the only facility left to host active NFL and Major League Baseball franchises. While the departure of the Oakland A’s, who are canvassing Oakland for a new ballpark site, seems likely to occur down the road, the move of the Raiders will mean that no NFL and MLB teams will share facilities, representing the culmination of a split that has unfolded for decades.

NFL and AFL teams using facilities that were built for baseball was not an uncommon practice in the 20th century. Many classic ballparks—including Fenway Park, Yankee Stadium, and Wrigley Field—were utilized for football along the way, and managed to establish their own legacies in the sport.

It was during the 1960’s that many of the venues associated with multi-purpose stadiums made their debuts. While some facilities, such as Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, and Cleveland Municipal Stadium, predated this period, the 1960’s were characterized by the multi-purpose “cookie-cutter” designs that took shape.

In 1961, D.C. Stadium opened, and with its large capacity in an enclosed seating bowl, was credited with being among the first to employ this design. By 1971, many other facilities would follow this formula, including Busch Stadium, Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, Three Rivers Stadium, Riverfront Stadium, and Veterans Stadium. It was in 1965 that the Astrodome opened, and ushered in an era of domed stadiums that hosted MLB and NFL action, with the Kingdome and Metrodome among the facilities following suit. Even the Superdome was floated as a potential MLB venue when it opened in 1975, though it ultimately hosted just a handful of MLB exhibition games and one season of minor league New Orleans Pelicans’ action.

Even if they did not employ the cookie cutter look in their opening, a few facilities would be enclosed over time, including Qualcomm Stadium, Candlestick Park, and Anaheim Stadium, the latter of which was expanded to accommodate the newly-arrived Los Angeles Rams prior to their first season at the venue in 1980. Some venues, including Shea Stadium, managed to avoid this fate during their years hosting both sports.

For many years, the Coliseum had the distinction of being open. While the facility may have never been hailed as a marvel from a design perspective, the unobstructed views of the Oakland Hills beyond the outfield wall gave the Coliseum a unique characteristic. That all changed in 1995, however, when the 20,000-seat expansion dubbed Mount Davis was constructed, and effectively eliminated the stadium’s view.

By the time Al Davis and the Raiders returned to Oakland from Los Angeles, a seismic shift had taken place in both the NFL and MLB. The Chicago White Sox and Baltimore Orioles moved into baseball-only facilities in 1991 and 1992, respectively, with the Orioles’ opening of Oriole Park at Camden Yards still credited today with influencing design trends among ballparks

Prior to that, however, a few NFL franchises had left their multipurpose stadiums behind. The Baltimore Colts played their last game at Memorial Stadium in 1983, before moving to Indianapolis, where the Hoosier Dome would open in 1984. While it was believed that both baseball and football could eventually be accommodated at the facility, it ultimately hosted NFL action and major events—including several Final Fours—before closing in 2008.

Football’s St. Louis Cardinals left Busch Stadium, and relocated to Arizona State University’s Sun Devil Stadium in 1988. During the 1990’s, several other franchises—including the Atlanta Falcons and Houston Oilers—would depart their multipurpose facilities a few years before their baseball co-tenants made their own exits.

During this decade, the trend has continued in both sports, with the San Francisco 49ers and then-Florida Marlins making their respective departures from Candlestick Park and Sun Life Stadium. In Toronto, the Rogers Centre saw its original football tenant—the CFL’s Argonauts—depart for BMO Field after the 2015 season, meaning that the facility that has also hosted the NBA and select NFL games along the way is now primarily used for baseball.

In the decades that these developments transpired, a few trends took place. Teams in both sports left behind their original domes and looked for retractable-roof venues, or at least fixed-roof facilities with a more modern design. Furthermore, the cookie cutters that had been built to replace many of baseball’s aging classics and accommodate the growing popularity of football had become obsolete. In their place, baseball- and football-only facilities were developed, with many cities embracing the concept of constructing the stadiums within close proximity of each other.

When the time comes for the Raiders and/or A’s to leave the Coliseum, it will mark the end of the era of shared MLB and NFL facilities. Perhaps for fans of both sports, the move to modern venues had its benefits, and the boom of new facilities has now unfolded for decades. That trend will continue with Las Vegas, but it is worth remembering the Coliseum’s place as the stadium from a previous era that, for better or worse, lasted as a testament to its time.

This article first appeared in the weekly Football Stadium Digest newsletter. Are you a subscriber? It’s free, and you’ll see features like this before they appear on the Web. Go here to subscribe to the Football Stadium Digest newsletter.