Back when the Super Bowl was not yet the Super Bowl, when it was still the AFL-NFL World Championship Game, choosing the game site was just slightly less organized than it is now.

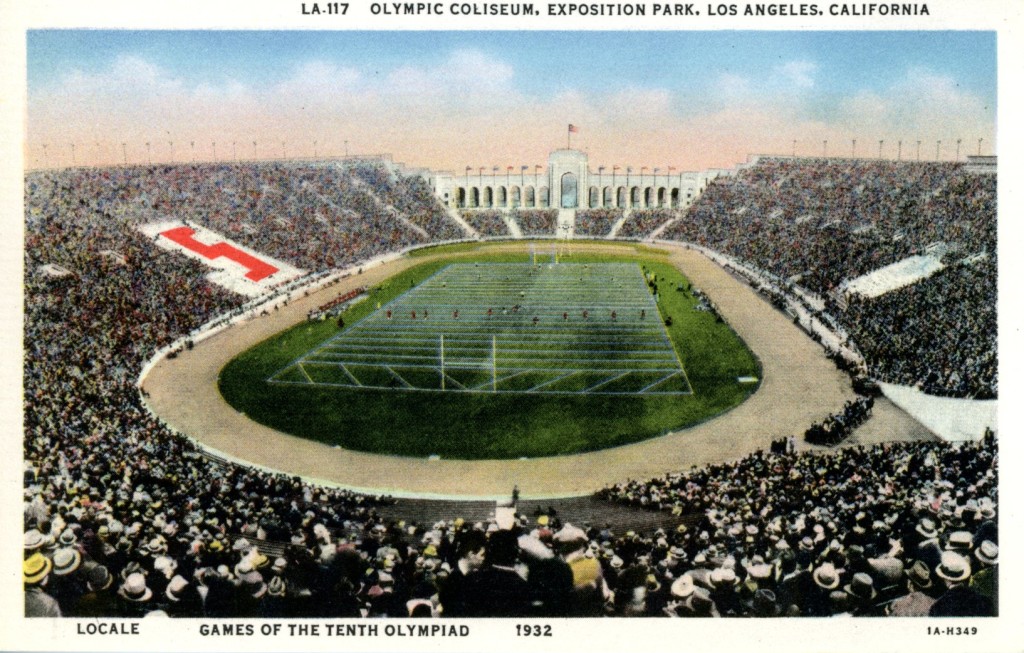

It was not until December 1, 1966, six weeks before the inaugural championship between the Green Bay Packers and Kansas City Chiefs, that the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum was selected to host. Things have changed. With Super Bowl LI less than a week away in Houston, we already know where Super Bowls LII (Minneapolis), LIII (Atlanta), LIV (Miami), and LV (Los Angeles) are due to be played.

That first year, it was NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle who served as the determining force behind the nod toward Los Angeles, nosing out lobbies from Pasadena, Houston, and New Orleans. Rozelle, by the way, had been born in Los Angeles County. But that first AFL-NFL World Championship Game drew less than 62,000 fans into the Coliseum, and so Rozelle opted to shift locations for 1968. He targeted the Miami Orange Bowl, a wise decision, as 75,000 fans attended the Packers’ second consecutive title win. The championship returned to the Orange Bowl in 1969, played before another crowd of over 75,000 — the first year the game was officially called the Super Bowl.

Rozelle made his intent known for the game to change between NFC and AFC host cities each year. Throughout the following decade, Miami, Los Angeles, and New Orleans wrestled the game back and forth, with unlikely factors swinging the decision. In March 1971, for instance, the Society of Air-Conditioning and Refrigeration Engineers was persuaded to change the opening day of their upcoming convention from January 18 to January 17. “That,” wrote Murray Chass in the New York Times, “freed 4,000 hotel rooms, making approximately 8,500 rooms available.” The Big Easy thus got the nod for 1972, overtaking rival presentations from Miami, Dallas, Los Angeles, Houston, and Jacksonville.

The decision-making underwent a shift at the very end of the decade, and a 28-year-old named Jim Steeg – the NFL’s Vice President of Special Events for over two decades – was right in the thick of things. “When I first got involved, the bids were very Chamber of Commerce,” Steeg told Rick Horrow and Karla Swatek, recounted in Beyond the Scoreboard: An Insider’s Guide to the Business of Sport . “[T]the ante was upped in March 1979. We were in Hawaii, and we were looking for sites for the Super Bowl in ’81, ’82, and ’83. Detroit really wanted the ’81 game, which New Orleans ended up winning. But Detroit came in – this was how crazy it was – and made a presentation, and it had a slide show, a video, and all this stuff up there. And all these owners, who you think are really tremendously sophisticated, were looking at this presentation and going on and on. That’s how Detroit got [the 1982 Super Bowl]. Their presentation materials were so far ahead of everybody else’s.”

Presentations, from style to substance, changed significantly to match Detroit’s standard or seek an alternate route to persuade the league. Philadelphia chose a blunter approach. The City of Brotherly Love made a bid for the 1987 Super Bowl with the proposal of a $2 million cash payment. (The NFL declined the offer.)

That oneupmanship has continued. Within the last decade alone: South Florida pledged yachts to the league’s owners. The city of New Orleans sent its bid in “handmade wooden boxes, engraved locally from Louisiana cypress and fitted with marine fixtures salvaged from Mississippi River docks,” according to the Times-Picayune. The city of Indianapolis organized 32 eighth-graders to personally bring its Super Bowl bid to each NFL owner. (The owners also received a shrimp cocktail from St. Elmo Steak House in Indianapolis.)The city of Tampa invited owners to golf with Arnold Palmer, with Palmer presenting each owner a putter at the outing. North Texas paid $1 million to the NFL to take care of all game-day costs. And the city of Phoenix commissioned iPads for each team owner — with each iPad individually featuring that owner’s team logo.

Bells, whistles, and Arnold Palmer aside, each city’s initial bid must satisfy the NFL’s Super Bowl requirements, a list that has grown from Rozelle’s unwritten pursuit of a warm-weather site that would attract snowbirds, to two pages in 1979, to today’s binder-jammed pages, estimated between 200-300 and released by the league to interested cities each November with an April deadline. Those specifications were made public on December 18, 2014, by Minneapolis Star-Tribune reporters Rochelle Olson and Mike Kaszuba, including 20 free billboards to be put at the NFL’s disposal, 35,000 free parking spaces, minimum 50-degree temperatures the week of the game (negated by an indoor climate-controlled facility), three free golf courses and two free bowling alleys, and a trustworthy cellphone signal at the team hotel, with temporary towers erected in case the signal was not trustworthy enough, to much, much more.

Those cities whose bids are accepted, moving them past the initial round, are invited to make their case in a 15-minute presentation to the owners meeting. In 2000, Jim Steeg estimated the average cost of such a presentation at $200,000. Once the presentations are made, the 32 owners conduct a secret-ballot vote. A minimum of two-thirds approval, 24 of 32 votes, is required to secure the Super Bowl bid.

And now we have arrived in the present.

It is nearly four years since May 21, 2013, when Houston won the vote to host this year’s Super Bowl; 13 years since Houston’s last time hosting, Super Bowl XXXVIII; 43 years since Houston’s first hosting duties, Super Bowl VIII at Rice Stadium, the first time a non-NFL stadium hosted the game; and 50 years since Los Angeles was first chosen by Pete Rozelle as the inaugural site with only six weeks to spare.

This article first appeared in the weekly Football Stadium Digest newsletter. Are you a subscriber? It’s free, and you’ll see features like this before they appear on the Web. Go here to subscribe to the Football Stadium Digest newsletter.