A distinction: The Collosseum is in Rome. The Coliseum is in Los Angeles.

That’s the 93-year-old Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, home to college football, the NFL, professional soccer, Super Bowl I, the Summer Olympics’ Opening Ceremony, Major League Baseball, Super Bowl concerts, the Special Olympics, the Super Bowl of Motocross, and, beginning again this autumn, the NFL’s newly-relocated Los Angeles Rams, moving from St. Louis.

As CBS Sports reporter Jason La Canfora mused on Twitter on January 12, 2016: “Indeed, hearing USC signed off on two NFL teams sharing LA Coliseum starting as soon as 2016. Wow”. Two pro teams? Not yet, but there will again be regular NFL action on Sundays at the historic Coliseum, and it’s a team with a familiar name and look.

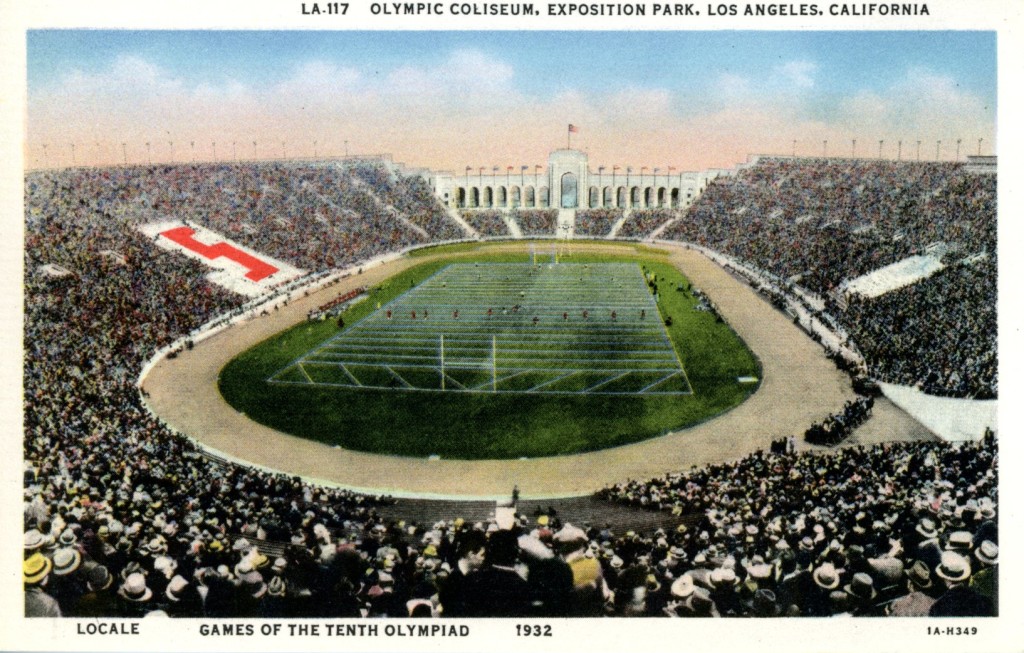

Venture back nearly a century. The Coliseum was the University of Southern California’s home from the start. Its Memorial name served as a tribute to local veterans of World War I, and its overall expense was upwards of $950,000. Its gates officially opened in June of 1923.

On October 6th, the L.A Memorial Coliseum hosted its first football game, a Week 2 Trojans victory over Pomona, 23-7. Spectators numbered 12,836. Still, the operators of the Coliseum pressed to expand. Stadium capacity grew from 75,000+ to 100,000+, with a torch added in preparation for the 1932 Olympic Games. (When the Games returned in 1984, the Coliseum became the first facility to host two different Olympics.)

13 years after those initial Summer Games, the Cleveland Rams sat atop the NFL. Coached by Adam Walsh, the Rams earned their way to a 9-1 record in 1945, outscoring the opposition 244-136 and dumping Washington in the Championship Game for the franchise’s first title. But Paul Brown, Otto Graham and the first-year Cleveland Browns of the AAFC loomed as competition entering the 1946 season; quarterback Bob Waterfield’s wife, actress Jane Russell, supplied a Hollywood connection; and owner Dan Reeves saw his chance to move to sunnier pastures and greater attendance figures.

There was a catch for Reeves, however, and it came with the L.A. Coliseum itself. There was no question that he wanted his Rams to play in the spacious stadium, which drew 100,000 fans every time the right two college teams got together. But the Coliseum presented a certain clause that needed to be met if the Rams were to use its grounds and sell tickets. “The Los Angeles Coliseum Commission,” wrote Tom Reed for Cleveland.com, “required the Rams to sign black players as part of the agreement for playing in the public venue.” Dan Reeves acceded to the request, signing Kenny Washington on March 21st and Woody Strode on May 7th. Washington and Strode became the first African-American players in the NFL since 1933. Because of the Coliseum’s contractual requirement, the Rams re-integrated football one year before Jackie Robinson made his Brooklyn Dodgers MLB debut.

On September 29, 1946, a crowd of 30,500 attended the first regular season game in Los Angeles Rams history. Two home games later, on November 10, a season-high assemblage of 68,381 cheered on the Rams in defeat against the powerful Chicago Bears. The new-look Los Angeles Rams finished the season with a 6-4 record, on the verge of further success.

The Rams went trailblazing down a different path in 1948. Artist/halfback Fred Gehrke was given the go-ahead by Reeves and coach Bob Snyder to take a paintbrush to the team’s brown helmets. His ensuing spiraling yellow ram’s horn on a blue background was the first logo ever added to a pro football helmet. A recollection from Gehrke, as quoted by Todd Radom: “[F]or two years I touched up the bonnets after every game. I kept a can of blue paint and a can of gold paint in my locker, and even took it along on road trips.”

Sporting their new identity, the good-looking Los Angeles Rams went to the NFL Championship Game three straight years, 1949-1951, defeating the Cleveland Browns for the ’51 NFL title before 57,000+ at the Coliseum.

Not long after, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley caught on to the success that could be gained from moving out west. Following the 1957 baseball season, away came the Dodgers, rolling in their moving trucks to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

The hometown difference was enormous. In 1957, the Dodgers posted a record of 84-70, good for third place in the eight-team National League, but they drew only 1,028,258 fans to old Ebbets Field and Roosevelt Stadium (located in Jersey City), the tenth-best mark in all of baseball. In 1958, the Dodgers’ record sank to 71-83, seventh place in the N.L. – but they drew 1,845,556, which placed second in the Major Leagues. In 1959, the Dodgers beat the Chicago White Sox in the World Series and drew over 2,000,000, best in baseball. Over 90,000 fans regularly attended specific games at a time, unmatched as a home ballpark in pro baseball’s history.

Unfortunately, the L.A. Memorial Coliseum was far more Olympic hosting site or football field than ballpark. Attempting to squeeze the arched nature of a baseball outfield into the Coliseums’ football-friendly dimensions caused the left field wall to sit only 250 feet away, compared to a 440-foot Death Valley in right-center. To combat the pain of cheap home runs, the Dodgers installed a 40-foot-tall screen in left. Deep line drives became singles; higher flies sailed right over the wall. An early story from Duke Snider about Willie Mays’s reaction, related by Rob Neyer in 2008: “Look where that right-field fence is, Duke. You couldn’t reach it with a cannon. You’re done, man! They just took your bat away from you.”

The Dodgers played four seasons at the Coliseum before relocating to Dodger Stadium in 1962. The Rams played 34 years at the Coliseum, before turning to Anaheim in 1980 and moving to St. Louis entering 1995.

The USC Trojans have remained the constant, playing at the Coliseum for 93 seasons.

In the intermediary, the NFL’s San Diego Chargers stopped by in 1960 for the year, and the Oakland Raiders transplanted themselves from 1982-1994. Soccer friendlies, matches and tournaments thrilled the patrons, particularly the CONCACAF Gold Cup in 1991, 1996, 1998 and 2000. The UCLA Bruins used the field from 1933-1981, working in concert with arch-rival USC. In the AAFC, the Los Angeles Dons lasted three years; the Los Angeles Wolves and L.A. Toros soccer teams lasted one season apiece, 1967; the Elton John-part-owned Los Angeles Aztecs soccer club played in the Coliseum in 1977 and 1981; the Los Angeles Express made waves for three seasons in the USFL, from 1983-1985; the Los Angeles Dragons football team petered out in 2000; the Los Angeles Xtreme crashed and burned with the XFL in 2001; and the Los Angeles Temptation weren’t tempting enough to survive past three years, 2009-2011.

It can be argued that it was the departure of the Chargers, Raiders and Rams that hurt the most. A city without an NFL team, it was ruled, was ineligible to host a Super Bowl. (Other intriguing NFL rules for a Super Bowl-hosting city: two bowling lanes and three golf courses.) The L.A. Coliseum has hosted two Super Bowls, each one memorable. The first was the inaugural game itself in 1967, the NFL-AFL World Championship Game, a convincing Green Bay Packers rout of the Kansas City Chiefs before 61,946 fans. The second was Super Bowl VII, held before 90,182, in which the Miami Dolphins completed the only undefeated season in the Super Bowl Era with a 14-7 doubling up of Washington.

With the arrival of the new Los Angeles Rams, Los Angeles is set to host Super Bowl LV in 2021, ready to stage another game to be etched into collective memory. The city is also making a bid for the 2024 Olympics, offering the Coliseum as its centerpiece.

To this end, plus the Rams’ arrival for a planned three-season run, but primarily for the continued success of Southern Cal football at its venerable home, the Trojans announced a $270 million renovation for the grand old structure. “The construction, which is to start after the 2017 U.S.C. season,” wrote Richard Sandomir in the New York Times in March, “will replace all of the seats (many are about a half-century old); add handrails; build a structure for luxury suites, club seats and a new press box; and improve wireless Internet connectivity and concession stands. When the work is finished in time for the 2019 Trojans season, capacity will have been reduced to about 78,000 [from 92,000].” But the renovation, Sandomir stressed, was not just about modernization. One side of the Coliseum is distinguished by august peristyle arches. These will be restored, the videoboards above them removed, the better to let the Coliseum’s original identity stand tall.

New and old, old and new. This is the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum’s legacy and identity: welcoming in its latest tenant’s energy, dreams, and tens of thousands of fans, all while steadily approaching a century of championship memories.

This article first appeared in the weekly Football Stadium Digest newsletter. Are you a subscriber? It’s free, and you’ll see features like this before they appear on the Web. Go here to subscribe to the Football Stadium Digest newsletter.